|

They

say, "You can't judge a book by its cover." In the case of

Marblehead's historic maritime treasure, Blackler's Salt Shed, you definitely

can't judge a building by its current state of shameful disrepair and

neglect. They

say, "You can't judge a book by its cover." In the case of

Marblehead's historic maritime treasure, Blackler's Salt Shed, you definitely

can't judge a building by its current state of shameful disrepair and

neglect.

In Marblehead, many of the great stories of history are found not merely

in books. Here history is still standing in the streets and along the

harbor's edge. Our old buildings with their drooping roof lines, crammed

together along narrow streets, teetering on the water's edge, and towering

majestically over the Town, all speak volumes about the lives, aspirations

and accomplishments of the great Marblehead tradition and of the caring

and involved people who built this community in the old days.

Central to the Town's legend is Marblehead's contribution to the American

revolution and the great courage and sacrifice it took to lead the building

of this great nation. The fact that George Washington came twice to

Marblehead to thank the Town for its revolutionary service, echoes through

history leaving no doubt of Marblehead's pivotal role. And yet, nearing

demolition, now all but abandoned, stands a symbol from that very era

when Marbleheaders reached for the stars and boldly led a grateful nation

to independence and freedom. Now the handiwork of William Blacker, who

rowed Washington across the Delaware himself, in a boat built with the

same hands, quietly inclines, almost metaphorically, towards a quiet

death by the sea. Blackler's salt shed, an admittedly modest, and run-down

building has had the Town twice now turn its back on its restoration.

Like an old library book whose dog-eared cover was replaced with a generic

institutional binding (and even that is worn and warped now) there are

still hidden within all the wonders of the original...waiting for the

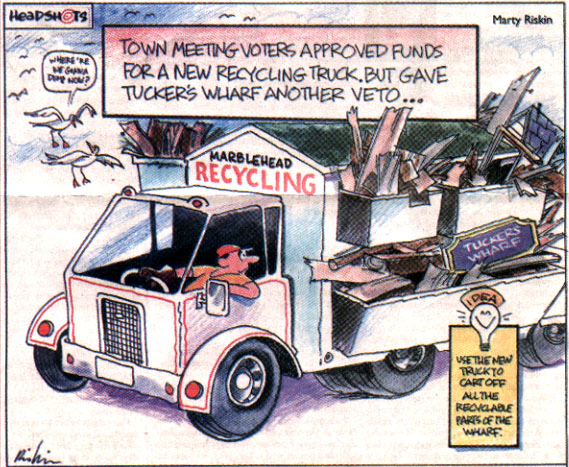

right hands to pick it up again. The Town voted for a new trash truck

but not to save Blackler's salt shed. But the little building that could

continues to inspire a small group of crusaders, who won't say die.

The struggle of the Friends of Tucker's Wharf, like the revolutionary

whose building they want to save, is a struggle against the odds, against

the apathy of many, and against the special interests that would sweep

history aside in favor of simple utility and cost effectiveness. And,

just like the history of Marblehead's revolutionaries, this story still

commands attention and there is still time to save a happy ending.

Marblehead's own story begins with fishing and quickly includes Blackler's

Salt Shed. There is no mistaking that simple truth. It was, after all,

the abundant cod that drew Europeans to New England, beginning probably

in the sixteenth century. They came in the spring, fished through the

summer, and took their catch home in the fall. To keep the fish from

spoiling, they removed the head and internal organs, rubbed them with

salt, and flaked them in the sun to dry. The bare rocks on the shore

of Marblehead were a natural place to accomplish this, away from the

eternal rocking of their small, but seaworthy boats.

The Salt Shed's story begins with William Blackler and his descendant's.

Blacker was a Marblehead fisherman whose date of birth, even the date

he came here from England's Channel Islands is not exactly known. He

was among those hardy souls who stayed in Marblehead through the winter,

after the fleet returned to Europe. He married the daughter of another

fisherman, John Codner, and they had five children, one of them also

named William. When Joan (or Johann or Jane) Codner Blackler died in

1701, their children inherited her father's land on the Great Harbor

next to Bartoll's Head (now Crocker Park).

The second William Blackler married Mary Rowles on December 18, 1701,

in Salem. Their son William III was baptized on August 27, 1704, and

he also ultimately became a fisherman. His wife Sarah bore five children,

of whom the second was named William and baptized on May 18,1740.

By this time, Marblehead's hardy fisherman had grown tired of the low

prices they were paid for their hard-won catches. Sometimes, England

wouldn't even buy their fish because of mismanagement by the Royal monopolies.

The fish brokers of other countries were not so constrained, and so

without official approval, some ships filled with Marblehead fish were

forced to go to France and Spain. There was an eager market for salt

cod among other English colonies too, particularly the islands whose

large populations of slaves growing sugar could not be sustained with

local produce. The fourth William Blackler may have begun in fishing

boats, but while still a young man he commanded much larger ships.

In an economy with a chronic shortage of money, it was common for Marblehead

captains to be paid with a share in the cargo. If the captains we shrewd

traders, they could make far more for themselves and the other owners

across the Atlantic. He could amass capital, and the entrepreneurial

William Blackler soon took shares in ships commanded by other men as

well and on the land he had inherited, he built several warehouses to

hold the return cargoes.

And, as you might have guessed by now, one of William Blackler's warehouses

is still standing: the one he built directly on the waterfront. It was

very sturdily built, to say the least, of 12" x 16" timbers mortised

together. It was built not only to withstand the ocean storms that swept

down the harbor, but also for the great weight of cargoes which filled

it in its heyday. The building is known to historians as Captain Blackler's

Salt House because one of the most precious commodities he traded was

salt. Without salt, the fish could not be preserved, and without preserving

the first for the ocean crossing, there would be no trade. Salt must

be kept dry, and so probably was stored on the second floor. A keg of

salt is very heavy and tons and tons of kegs on the second floor meant

strong rafters and framing: strong enough to last more than 230 years,

and survive the toughest and most violent storms the Atlantic Ocean

can serve up. But, will the handiwork of William Blacker prove strong

enough to withstands the storm of apathy and the sure, swift hands of

expediency?

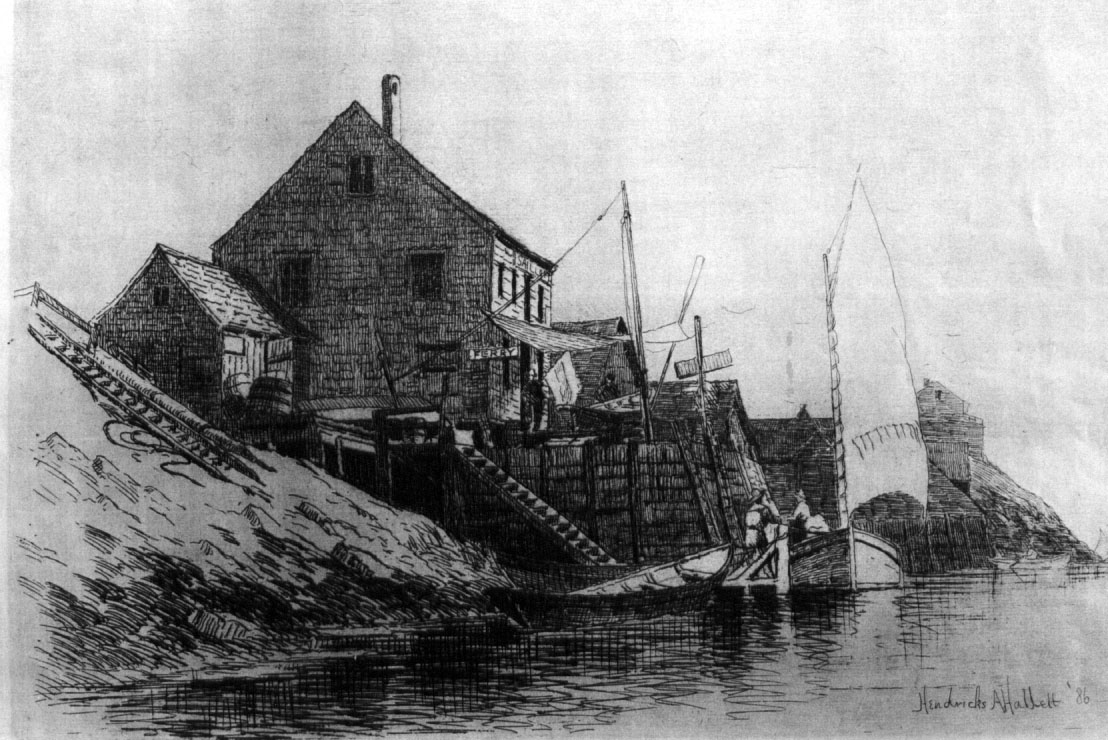

The salt house is perched on a shallow outcropping of low granite that

lines the Town-side shore near the strategic middle of Marblehead Harbor.

It is nestled on the granite at the rear, and on the stubs of ship's

masts in front. A thick stone seawall was built around it, and the whole

area was filled in to make the building more stable, and to allow the

largest ships to tie up right next to it. The men who built the salt

shed took such pride in their work that they carved the date they finished

the building in one of the huge posts: "1770." Two hundred and thirty

years later, their handiwork and craftsmanship is still intact: 60 posts

and beams frame the original construction as solidly jointed together

today as they ever were. Even the ship's masts are still there underneath

it, secure and solid.

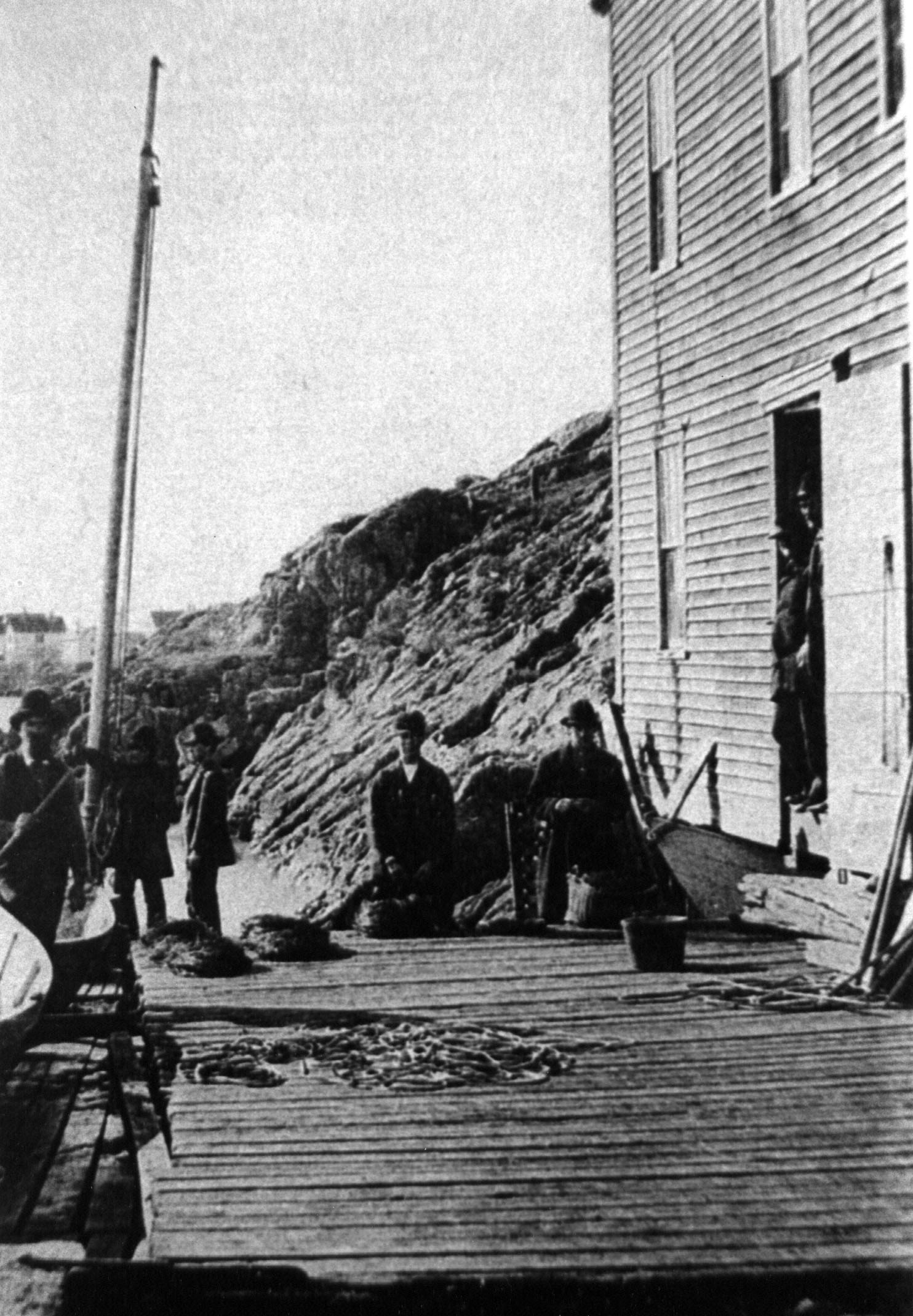

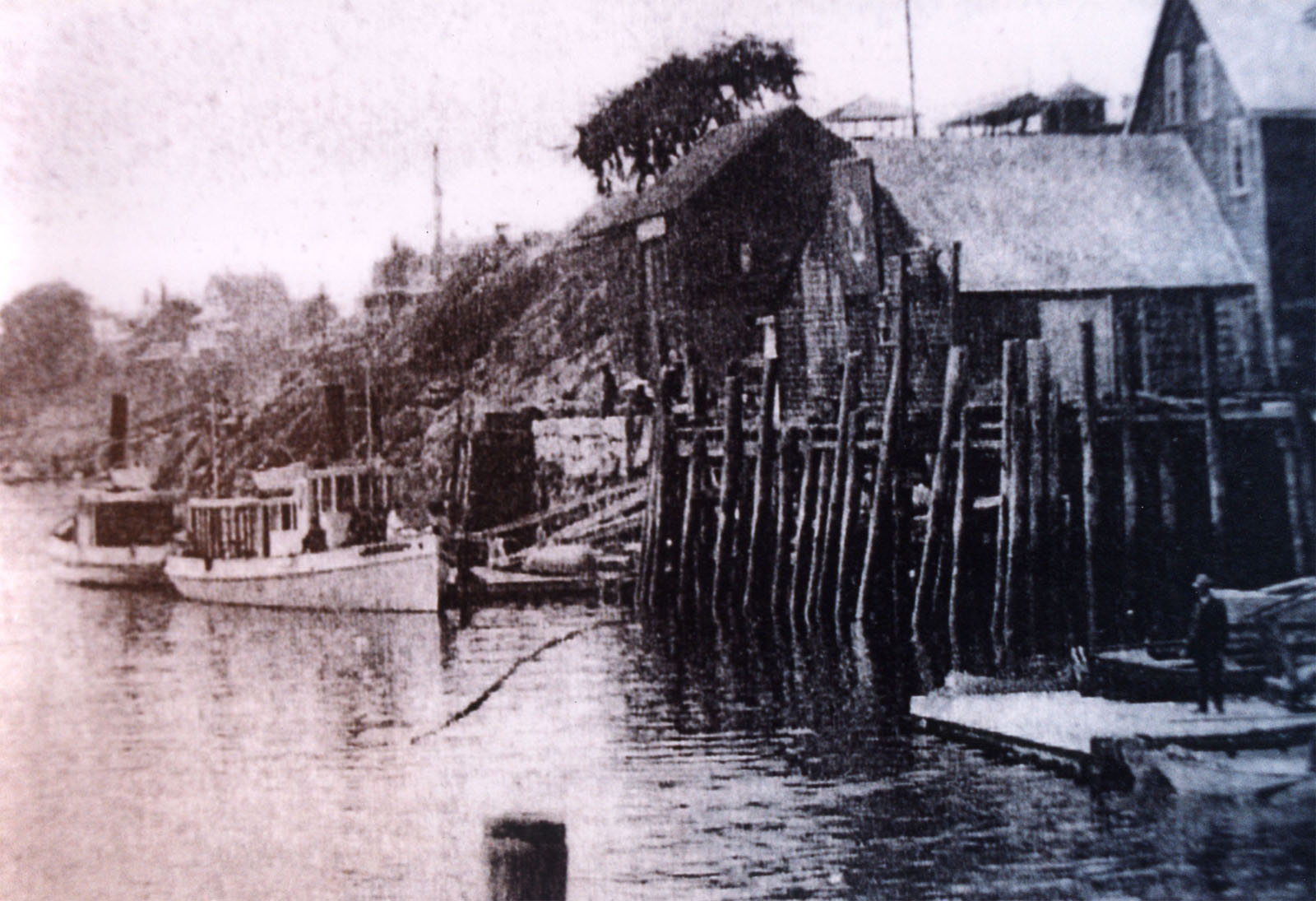

As the source of salt, Blackler's warehouse must have been the figurative

as well as literal center of the harbor. Before heading out, every fishing

boat would have to stop there. The oldest pictures and drawings, from

the 1850's, show all manner of fishing boats from dories to schooners,

gathered around the historic little building. As another historic note:

he first recorded use of the word "dory" is found in the account book

of a Marblehead boat builder, and Marbleheaders pioneered the first

use of these "dories" on schooners. The large schooners would

carry the dories to the fishing banks, and once there the fishermen

would fan out in the smaller boats, dories, Ñ on the open ocean. It

was hard and dangerous work. And all Marblehead fishing voyages started

down at Blackler's Salt Shed, or at the very least stopping at the shed

was as routine as anything could have been in the days when Marblehead

was a true seafaring coastal New England town with most, if not all,

of its able-bodied men at sea.

Old pictures also show a special, some say, "curious," door

on the second floor of Captain Blackler's Salt House. It resembles the

ordinary door on the first floor, but it is offset, and there are no

stairs to reach it. The kegs of salt probably were hoisted out of that

door, into the schooner tied up below. The windows were placed the  same

way Ñ wherever light was needed. The rules of symmetry were strictly

followed in the grand old houses of Town, but in the salt house, and

around the waterfront, symmetry was cast aside for pure functionality

creating the historic and perhaps, now, "quaint architecture of

the waterfront, so distinctly historic, so absolutely authentic, and

so, well, so Marblehead...that as the years have gone by some of us

have perhaps taken them for granted and so much so that now they seem

derelict and irrelevant. How looks can deceive! same

way Ñ wherever light was needed. The rules of symmetry were strictly

followed in the grand old houses of Town, but in the salt house, and

around the waterfront, symmetry was cast aside for pure functionality

creating the historic and perhaps, now, "quaint architecture of

the waterfront, so distinctly historic, so absolutely authentic, and

so, well, so Marblehead...that as the years have gone by some of us

have perhaps taken them for granted and so much so that now they seem

derelict and irrelevant. How looks can deceive!

The trouble is that the symmetrical and glorious grand houses that are

so treasured and preserved do not give a true impression, a complete

depiction of the Town of those early days. Captain Blackler's other

fishing warehouses are long gone, forgotten. All the other fishing and

trading warehouses of the Town have also disappeared. In fact, Captain

Blackler's salt house is the last 18th century commercial building in

its original place on Marblehead's waterfront, and, unbelievably it

is the last one in all of New England! Now when one looks at Marblehead

from the sea, its early history is barely visible and fading out every

day. Fort Sewall sit stands triumphantly at the mouth of the harbor

but it is closely wrapped on both sides by one building that was moved

to the waterfront and wrapped in porches (now condominiums), and stately

but by comparison detracting modern residences on the other. Fort Sewall

and Blackler's humble little salt shed: they are all that's left of

the old historic structures on the waterfront.

By 1770, New England seamen and traders like William Blackler were impatient

with the management of the colonial  economy

from far away London. English law required that all colonial trade go

through the mother country, and almost every movement of goods was taxed

and taxed again. For most of his life, Blackler had traded directly

with the other colonies, and even with the enemies in England's perpetual

wars for domination of Europe. Marbleheader wily ways of distracting

and dodging the tax collector are the stuff of legends. Suffice it to

say that Marbleheaders developed a thriving independent trade, and a

truly independent frame of mind. Blackler was a member of the Council

that organized an American boycott of English goods. economy

from far away London. English law required that all colonial trade go

through the mother country, and almost every movement of goods was taxed

and taxed again. For most of his life, Blackler had traded directly

with the other colonies, and even with the enemies in England's perpetual

wars for domination of Europe. Marbleheader wily ways of distracting

and dodging the tax collector are the stuff of legends. Suffice it to

say that Marbleheaders developed a thriving independent trade, and a

truly independent frame of mind. Blackler was a member of the Council

that organized an American boycott of English goods.

In 1773, brave and committed William Blackler raised a company of militia,

equipping and training the men at his own expense. Two years later,

he enlisted in the Continental Army and his minutemen became part of

General John Glover's famous regiment. On 22 June 1775, he was commissioned

a Captain of the army, and thus had earned the title on both land and

sea. Earlier that year, a British raiding party had landed on Devereux

Beach with the intent of seizing a cache of arms rumored to be in Salem.

Blackler's men intercepted them, and only adroit and intense negotiation

by Parson Barnard prevented the first shots of the Revolution from being

fired in Marblehead instead of Concord.

The

role of Glover's Regiment in the Revolutionary War was pure glory, and

a deserving subject for a host of books describing it from every angle.

Most of the action took place near New York. General George Washington

had great need of the seafaring skills of Glover's Mabrlehead men, and

William Blackler was Captain of the boats. When the British trapped

Washington's army on Long Island, the Americans escaped in Blackler's

boats. On Christmas Eve 1776, it was Blackler's boats that ferried the

army across the Delaware River to win the crucial first victory of the

war. General Washington rode in Blackler's own boat. The

role of Glover's Regiment in the Revolutionary War was pure glory, and

a deserving subject for a host of books describing it from every angle.

Most of the action took place near New York. General George Washington

had great need of the seafaring skills of Glover's Mabrlehead men, and

William Blackler was Captain of the boats. When the British trapped

Washington's army on Long Island, the Americans escaped in Blackler's

boats. On Christmas Eve 1776, it was Blackler's boats that ferried the

army across the Delaware River to win the crucial first victory of the

war. General Washington rode in Blackler's own boat.

Marblehead was exhausted by the Revolution. The townspeople gave so

much of their fortunes and so many men were lost or injured that the

town slumped into an economic depression after the country's victory.

The doors of the ocean trade were wide still open, however, and Captain

William Blackler went back to sea again, this time to the sugar plantations

of the Caribbean. It is recorded that on December 27, 1790, he brought

the 98 ton schooner Dolphin into Marblehead laden with sugar, cotton,

coffee, molasses, salt (700 barrels of it) and one cask of rum, all

on his own account. The next time Dolphin landed a similar cargo, on

April 10,1793, it was his son William, V, in command.

Now in his 50's, the William Blacker seems to have turned the sailing

over to his son and concentrated on the trading business. Locally, he

bought fish, beef, rum, cider and lumber for export, and he imported

sugar from Guadeloupe, St. Martin and Martinique, wine from Bordeaux,

iron from Sweden, rope and canvas from Russia, glassware from Italy,

and window glass, lead, bed ticking, and linen from other continental countries.

He also bought tea, rice and other commodities from his fellow merchants,

and traded them in the Caribbean and Europe. He prospered, and built

a stylish brick mansion that still stands on Pearl Street. After Captain

William Blackler died on June 15, 1818, his son continued the business.

glass, lead, bed ticking, and linen from other continental countries.

He also bought tea, rice and other commodities from his fellow merchants,

and traded them in the Caribbean and Europe. He prospered, and built

a stylish brick mansion that still stands on Pearl Street. After Captain

William Blackler died on June 15, 1818, his son continued the business.

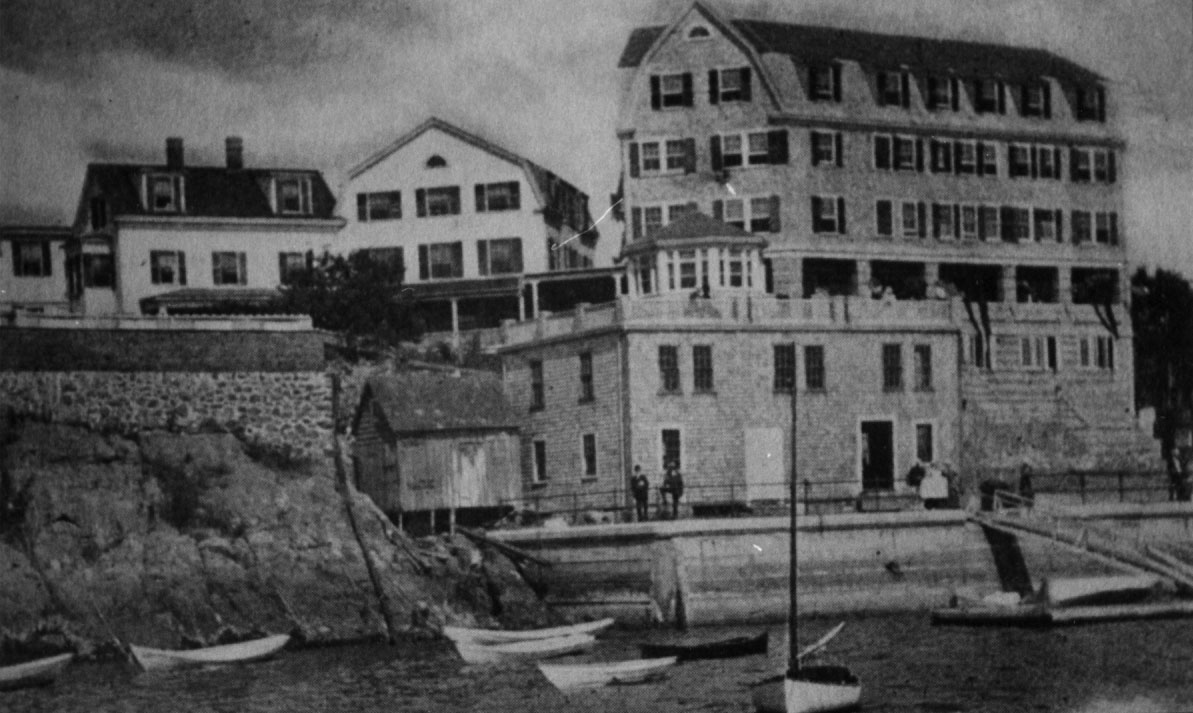

The Great Gale of 1846 decimated the fishing fleet of Marblehead, and

the industry gradually shifted to larger and larger boats, and to the

larger port of Gloucester. International trade also shifted to larger

ships and ports, and Marblehead began to put as much effort into making

shoes as catching fish. The growing urbanization of the rest of the

country, accelerated by the brutal Civil War, opened a new chapter for

Marblehead, and, in turn, a new story for Captain Blackler's Salt House.

Crowded and unsanitary cities became unbearable in the heat of summer,

and those who could afford it, the rich elite, began to seek relief

in small, cooler coastal towns such as Marblehead. The open farmlands

on Marblehead neck slowly were dotted with resort hotels, and then summer

homes. Yachting became a national passion, and for the great sailing

and steam yachts of the late nineteenth century, Marblehead's safe,

deep and picturesque harbor was de rigeur for cruises through

New England waters. Soon, the little town was being called the yachting

capital of America.

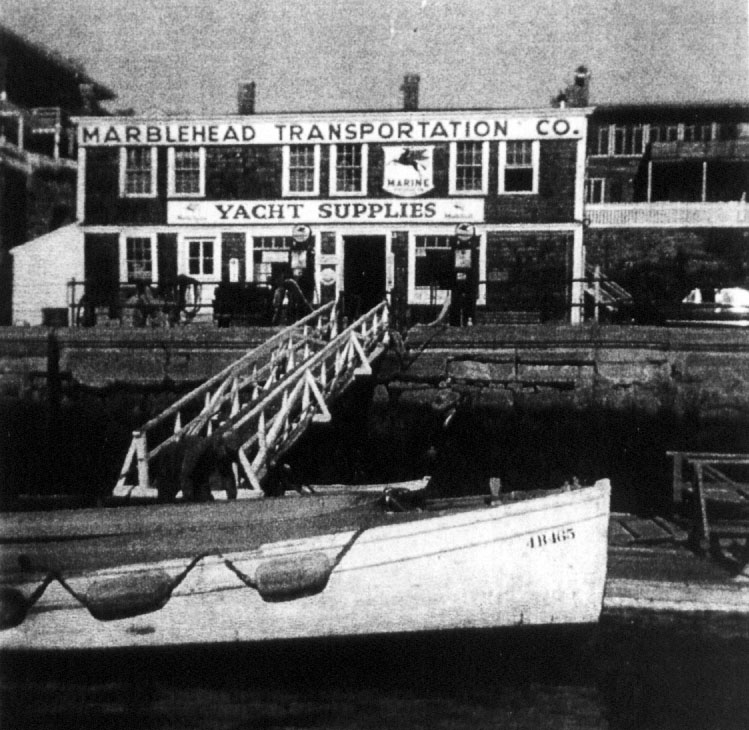

Summer visitors needed a means to get from the railroad to the hotels,

and all those yachts needed supplies. The first man to operate a ferry

in Marblehead harbor  was

Philip B. Tucker, a direct descendant of the Samuel Tucker who won great

fame as a naval commander during and after the Revolution. His ferry

was a large catboat (an open, broad-beamed boat with a single mast and

sail). When needed, he supplemented the catboat with dories in which

people rowed themselves around the harbor. "Phip" Tucker also operated

a chandlery, delivering all sorts of supplies from coal to food to resupply

the large yachts. He called his enterprise the Marblehead Transportation

Company, and his base of operations was, of course, Captain William

Blackler's Salt House. The road to the salt house was named Ferry Lane,

and everyone referred to the ferry landing as Tucker's Wharf. Some of

the greatest names in yachting history and at least one president (Grover

Cleveland) landed at Tucker's Wharf. But in truth, when Marblehead was

the Yachting Capital of America, Blackler's Salt Shed and the Transportation

company, was the center of yachting in Marblehead. was

Philip B. Tucker, a direct descendant of the Samuel Tucker who won great

fame as a naval commander during and after the Revolution. His ferry

was a large catboat (an open, broad-beamed boat with a single mast and

sail). When needed, he supplemented the catboat with dories in which

people rowed themselves around the harbor. "Phip" Tucker also operated

a chandlery, delivering all sorts of supplies from coal to food to resupply

the large yachts. He called his enterprise the Marblehead Transportation

Company, and his base of operations was, of course, Captain William

Blackler's Salt House. The road to the salt house was named Ferry Lane,

and everyone referred to the ferry landing as Tucker's Wharf. Some of

the greatest names in yachting history and at least one president (Grover

Cleveland) landed at Tucker's Wharf. But in truth, when Marblehead was

the Yachting Capital of America, Blackler's Salt Shed and the Transportation

company, was the center of yachting in Marblehead.

A steam ferry named Escort, probably "Phip" Tucker's, was wrecked on

Marblehead Neck on June 8, 1882. It was replaced with two steam launches,

and when Tucker died on October 15, 1900, other men were ready to take

over the business. By this time, the salt house was 130 years old and

in need of renovation. The houses behind it were replaced by the Fountain

Inn, a four-story wooden hotel catering to the growing summer trade,

in 1903. Captain Blackler's Salt House became part of the project, and it was

given a new "cover," including shingles to replace the old hand-split

clapboards, and new doors and windows placed symmetrically. Its gabled

roof was cut off as well, and the new flat roof became a patio where

hotel guests took tea in the afternoon, and danced in the evening. Inside,

it was still the Marblehead Transportation Company, stocked with yacht

and fishing supplies, and used for repairing boat gear. A quaint octagonal

ticket office was built for the ferry service. As internal combustion

engines became more common, gasoline pumps were installed in front of

the old salt house.

Captain Blackler's Salt House became part of the project, and it was

given a new "cover," including shingles to replace the old hand-split

clapboards, and new doors and windows placed symmetrically. Its gabled

roof was cut off as well, and the new flat roof became a patio where

hotel guests took tea in the afternoon, and danced in the evening. Inside,

it was still the Marblehead Transportation Company, stocked with yacht

and fishing supplies, and used for repairing boat gear. A quaint octagonal

ticket office was built for the ferry service. As internal combustion

engines became more common, gasoline pumps were installed in front of

the old salt house.

Yachting boomed after World War II, the Transportation Company prospered,

and a whole generation of Marbleheaders were introduced to the water

in a new way, working on the docks, on the yachts and in the ferries

servicing the harbor as well as fishing. Two large plate glass windows,

the latest thing, were installed on the first floor of the salt house.

By the time of the salt house's bicentennial, it needed a new "cover"

again. In 1973, the shingles, many of the windows (including the plate

glass ones) and the doors were replaced. Underneath, the sills were

replaced, and the lighter new ones reinforced with concrete in the rear

and new pilings. The frame had developed a pronounced lean toward the

water,  which

was not corrected, and the new door projected four inches from face

of the building. which

was not corrected, and the new door projected four inches from face

of the building.

Then, yachting began to change, and as the proprietors of the Marblehead

Transportation Company aged, the company's fortunes began to fade. Some

of the land on the wharf and the land behind was developed as three

and four-story condominiums, effectively hiding the salt house from

the town. By 1992, the Transportation Company was bankrupt, its principal

asset, a waterfront lot, had been irresponsibly contaminated with oil

and gasoline. The seawall was crumbling and a sad-looking, tired but

historic building was leaning towards the harbor and obscurity.

In order to preserve access to the water for all and keep marine businesses

in Marblehead (the alternative always being more condominiums and construction,

apparently ), the Town actually bought Tucker's Wharf in 1993, just

as it had bought several waterfront boatyards in previous years. The

initial asking price was $732,000.00, and the debate raged at Town Meeting

concerning the price as much as the merits of the land. A price of $695,000.00

was approved by a special Town Meeting that fall, the bond to be paid

from the "enterprise fund" of the Harbors & Waters Board. In addition,

$425,000.00 for the rebuilding of the seawall was appropriated.

The contamination of the land proved more widespread than thought, but

additional sums for cleanup of $65,900 and $31,000 were approved in

1996 and 1997, making the total cost of repairing the seawall and cleaning

up the land $521,900. To reduce the impact on the Harbors & Waters

Board, the Town applied for a grant from the Massachusetts Highway Department

in 1996. Since Captain Blackler's Salt House had been a ferry terminal,

and therefore an important historic transportation building, it qualified

for a special fund, and the application was rated very high. However,

the Harbors & Waters Board planned to move the Harbormaster's office

a half-mile up the shore into the salt house, and a municipal office

would disqualify the application. The amount of the grant would have

been $762,000.00, enough to pay for the seawall and substantial renovations

of the historic building. It would have saved the balding and save the

Town a lot of money at the same time.

With the seawall finished but having absorbed the rest of the  harbor

surplus, the Harbors & Waters Board proposed a public-private partnership

to Town Meeting in 1998. The proposal included tearing down Captain

Blackler's Salt House and allowing a private developer to erect a modern

commercial building on the site. After a specified number of years,

title to the building would be given to the Town, and the developer

would lease the building thereafter. This proposal was hotly debated

and roundly defeated, and requirements were added, to protect the building

in the future, that the Old and Historic District Commission must review

any subsequent plans, and that the future of Tucker's Wharf must be

decided by a vote of Annual Town Meeting. harbor

surplus, the Harbors & Waters Board proposed a public-private partnership

to Town Meeting in 1998. The proposal included tearing down Captain

Blackler's Salt House and allowing a private developer to erect a modern

commercial building on the site. After a specified number of years,

title to the building would be given to the Town, and the developer

would lease the building thereafter. This proposal was hotly debated

and roundly defeated, and requirements were added, to protect the building

in the future, that the Old and Historic District Commission must review

any subsequent plans, and that the future of Tucker's Wharf must be

decided by a vote of Annual Town Meeting.

The Harbors & Waters Board retained an architect to investigate

alternatives to simply demolishing the salt house, and then awarded

a contract valued at $31,000.00 for an architect to draw up the plans

for renovation. In light of estimates prepared from those plans and

the recommendations of the Harbors & Waters Board,, Town Meeting

voted in 1999 to appropriate $450,000 for "remodeling, reconstruction

and extraordinary repairs." To reduce the strain on the Harbors &

Waters Board's budget, the Board of Selectman decided to pay half the

cost of the two $450,000 bonds issued for Tucker's Wharf from general

tax revenues, initially $80,000.00 and declining approximately $2,500.00

every year since.

Before bids could be solicited from contractors, the original architect

died. After some months' delay, bids were submitted ranging from $417,000.00

to $900,000.00, with only the low bidder bothering to actually come

out and inspect the  building.

Explanations for the high bids ranged from lack of interest among contractors

due to the building boom then ongoing , to defects detected in the plans

themselves, such as requiring that new foundations be built without

raising or moving the building, and specifying a steel frame around

the outside without investigating whether the historic timbers could

still do their job. The Harbors & Waters Board voted to not accept

any of the bids. Consequently, the Board had to pay a stiff fine

of $30,000.00 for not using the funds appropriated within the year after

the Town Meeting vote. building.

Explanations for the high bids ranged from lack of interest among contractors

due to the building boom then ongoing , to defects detected in the plans

themselves, such as requiring that new foundations be built without

raising or moving the building, and specifying a steel frame around

the outside without investigating whether the historic timbers could

still do their job. The Harbors & Waters Board voted to not accept

any of the bids. Consequently, the Board had to pay a stiff fine

of $30,000.00 for not using the funds appropriated within the year after

the Town Meeting vote.

By 2001, the Harbors & Waters Board had decided to ask for either

an additional $200,000.00 or permission to demolish the salt house.

Their request was amended on Town Meeting floor, with an overwhelming

vote, to reject and eliminate any possibility of demolition, and then

the $200,000.00 was approved by Town Meeting. The vote to appropriate

was contingent on passing a Town-wide debt-exclusion override approval.

But at the polls, in a very low turnout election, the override request

failed. Captain Blackler's Salt House remained empty and neglected,

but the override failed by only a few votes and Tom Meeting's resolve

was encouraging. With standing water on its roof the most visible threat

to its continued survival, the real threat continued to be the lack

of true commitment on the part of the Town's boards and apathy at the

polls. But there were other positive trends coming.

An

informal group of citizens, the Friends of Tucker's Wharf, proposed

rethinking the project and identified simple changes that promised savings

of more than $100,000. The cost of drawing new plans could have been

as much as $25,000.00, however, and the Harbors and Waters Board voted

to not spend any more money until they felt sure of completing the project.

They took the same plans to the next Town Meeting and made a second

request for additional tax money, $250,000.00 this time. Again it passed

at Town Meeting overwhelmingly, but a second article demanding that,

if the override failed, the harbors & Waters Board must spend the

money it had to save the building even if the funds would not go all

the to the completion of the plans. (And there was dispute on this point,

some feeling that it could easily be done with the money in hand and

others doubting it. But it was clear that if the money in hand was spent,

it would advance the exact plans of the Harbors & Waters Board's

architect, if not all the way, a long way.) But, again, the vote failed

in at the polls by a few hundred votes. Now 232 years old, the historic

salt house is still empty, neglected, and yet is sound and strong at

the heart of its construction; the handiwork and craftsmanship of the

revolutionary hero, William Blacker. An

informal group of citizens, the Friends of Tucker's Wharf, proposed

rethinking the project and identified simple changes that promised savings

of more than $100,000. The cost of drawing new plans could have been

as much as $25,000.00, however, and the Harbors and Waters Board voted

to not spend any more money until they felt sure of completing the project.

They took the same plans to the next Town Meeting and made a second

request for additional tax money, $250,000.00 this time. Again it passed

at Town Meeting overwhelmingly, but a second article demanding that,

if the override failed, the harbors & Waters Board must spend the

money it had to save the building even if the funds would not go all

the to the completion of the plans. (And there was dispute on this point,

some feeling that it could easily be done with the money in hand and

others doubting it. But it was clear that if the money in hand was spent,

it would advance the exact plans of the Harbors & Waters Board's

architect, if not all the way, a long way.) But, again, the vote failed

in at the polls by a few hundred votes. Now 232 years old, the historic

salt house is still empty, neglected, and yet is sound and strong at

the heart of its construction; the handiwork and craftsmanship of the

revolutionary hero, William Blacker.

As central to New England history as fishing is, to mount an exhibition

on fishing, local museums and historians have to rely on paintings and

models (many gathered by the great Marblehead collector Russell W. Knight).

Only little bits and pieces of gear and the old fishing artifacts now

survive. New England's greatest fishing museum, Mystic Seaport, has

concentrated on the 1880's for its displays, because, in truth, so little

material older than that has survived.

Captain Blackler's Salt House is an original artifact of 1700s fishing

industry and era in its original location. More than that, it is not

just the substance, but also the spirit of the place that still stands

in here in Marblehead. It is a direct, tangible and vitally important

link to the reason Marblehead and New England were founded and succeeded.

The story of Blackler's Salt Shed is the story of the Revolution, of

summer resorts and yachting, of Marblehead. Its cover looks tattered

now, but it is still Town property,under the care and custody of the

people of Marblehead. And if enough of the Town's people speak up, they

could still cause a little bit of a revolution once again: saving our

history and preserving our unique and irreplaceable heritage. The little

building that could is waiting for you.

To contact The Friends of Tucker's Wharf, email the author

by clicking here.

|